Just Like Burgundy Wine, Tea Has Terroir

Boulder attracts a wealth of engaging community events, from the Bolder Boulder — one of the largest and most prestigious 10k races in the country — to the Jaipur Literature Festival (a worldwide event celebrating literature, which has a vibrant Boulder presence) and the Flatirons Food Film Festival.

One of our favorites is Boulder Burgundy Festival, which explores the sublime wines from France’s Burgundy region: principally, Pinor Noirs for reds (the region also grows Gamay, which is fermented into Beaujolais and can be fabulous), and Chardonnays (the other Burgundy white is Aligote, a bright, zesty wine). The festival runs this week, from October 22 to 24.

What does wine have to do with tea? Read on!

Wines lovers around the world obsess over Burgundies. Well-wrought Chardonnays from Burgundy are somehow simultaneously bold, elegant and subtle. It’s not uncommon for Master Sommeliers to say white Burgundy is the wine they would choose if they could have just one more glass for the rest of their lives. The Pinot Noirs age exceptionally well, evolving into startlingly complex spectacles of aroma and flavor. They offer notes like forest floor and mushrooms, cedar and cherry, tobacco and raspberry. They are glorious.

Terroir — the combination of soil, climate, elevation, geographic location, vine age (some Burgundy vines are more than 120 years old) and much more — is one of the factors that makes wines from Burgundy so transcendent. The wines reflect the land. This happens around the world, but is especially pronounced in Burgundy.

Industrial Wine and Tea Lack Terroir

But most commercial wine is divorced from terrior. The $5 bottle of red from California’s Central Valley might be quite tasty. But it’s not a reflection of place and history.

It’s the same story with tea. When you snag a box of 100 tea bags from the grocery store for $10, you’re not communing with a tea plantation’s terroir.

Good news, friends — we don’t import industrial tea! Most of our traditional tea comes from small farmers across Asia. Which brings us full circle, back to the wine-tea connection. Some teas do indeed reflect terroir. When you try a few teas that grow near one another and they yield different flavors, it’s the terroir that often makes the difference, unless the post-harvest steps diverge dramatically.

As total tea nerds, we thrill to exploring teas from China, a place where tea captures a large part of culture. Tea is ancient in China. One tea shrub in China’s Yunnan Province, thought to be the birthplace of tea, is estimated to be 3,200 years old.

The diversity of flavors that bloom from leaves harvested from the same plant — Camellia sinensis — never cease to intrigue us. Exploring tea from small farms across China, as well as places like Japan and India, yields a vast range of flavors: fresh-cut grass, apricot, cherry blossoms, toast, cocoa and much more.

As we sink into autumn and begin the steady march toward Thanksgiving and the holidays, let’s explore tea terroir with a trio of teas from China that we think capture their terroir.

Tea Terroir: Da Hong Pao

Any discussion of terroir and tea must address China’s Wuyi Mountains, in Fujian Province. There, teas known as “rock oolongs” grow. They get their name because of their terroir — the mountainous soil indeed is rocky, and it influences the teas’ flavors. Among other things, the parsimonious soil leads to fewer leaves. As a result, tea flavors are more concentrated.

Da Hong Pao means “Big Red Robe” in Chinese, and it is the most famous of all rock oolongs. Records of Da Hong Pao date back to the early 18th century. The tea has a strong fragrance and a rich, roasted taste, followed by a pleasant, lingering sweetness. As with most teas from the Wuyi Mountain region, Da Hong Pao undergoes fairly heavy oxidation and offers a subtle smokiness along with stone-fruit notes.

Tea Terroir: Black Peony

Known for its intense floral fragrance and stone-fruit flavor, Black Peony is a rare black tea that grows in Hunan Province’s Wuling Mountain region. The region is best-known for the Zhangjiajie National Forest, a sprawling area of dense forest and foliage with pillar-shaped mountain peaks, waterfalls and clouds and mist year-round. It’s an arresting landscape, and certainly contributes to Black Peony’s unique flavor.

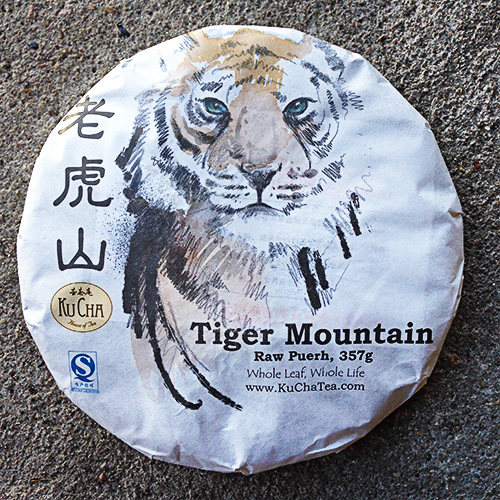

Tea Terroir: Tiger Mountain

Once again we turn to mountains, in this case Tiger Mountain in China’s Yunnan Province. Tiger Mountain tea is a raw pu-erh cake, crafted from leaves of wild tea trees. As pu-erh is a fermented tea, it not only is delicious brewed immediately — Tiger Mountain can also age for decades. Tea enthusiasts who thrill to pu-erh remind us of Burgundy wine fanatics, who often wait for many years before opening a bottle. As with Burgundy, age adds complexity to good raw pu-erh cakes like Tiger Mountain. This tea brews bright and bittersweet, with strong Cha Qi (tea energy) and a noticeable pear fruitiness. Our Tiger Mountain is still young, from 2017. It’s wonderful to sip it now, but it will evolve with further aging.